Learning Objectives

The learning objectives for Ideal Indirection are:

- Virtual Memory

- The virtual address translation process

- Memory Management Unit (MMU)

- Page Tables

- Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

Overview #

In this assignment, you will be working on managing a mapping of a 32-bit virtual address space to a 32-bit physical address space with 4 KB (kilobyte) pages.

Each component of virtual memory has been split up into several files to help you build a mental model of virtual memory.

Reading through these files will help you understand the roles of the different hardware and software involved in managing virtual memory.

You will only have to write two functions in mmu.c, but it requires a good understanding of the virtual memory translation process and decent understanding of the rest of the provided code.

How To Tackle This Assignment #

-

First, you will need to understand how the virtual memory translation process works. You will be writing functions to translate virtual addresses into physical addresses, so a good first step is to understand that process. The coursebook has details on this process, and feel free to ask about this if you are unsure.

-

Then, you will want to understand how we simulate the different components of a computer in this assignment. The header files describe the various structs involved in this simulation, as well as their member variables. At a minimum, you also need the following helper functions to complete the assignment:

- tlb_flush() in tlb.h

- tlb_add_pte() in tlb.h

- tlb_get_pte() in tlb.h

- mmu_raise_segmentation_fault() in mmu.h

- mmu_tlb_miss() in mmu.h

- mmu_raise_page_fault() in mmu.h

- ask_kernel_for_frame() in kernel.h

- get_system_pointer_from_pde() in kernel.h

- read_page_from_disk() in kernel.h

- get_system_pointer_from_address() in kernel.h

- find_segment() in segments.h

- address_in_segmentations() in segments.h

However you are free to use whichever other helper functions you’d like. The source code for these functions have been given to you; you should be able to get a grasp on the whole model just by reading the header files, but if you are interested to see how we model the different components, you can read the source code.

- Once you have a good mental model, you will want to plan out the steps your code needs to perform. Start by following the pseudocode below:

- Use pid to check for a context switch. If there was a switch, flush the TLB

- Make sure that the address is in one of the segmentations. If not, raise a segfault and return

- Check the TLB for the page table entry. If it’s not there:

- Raise a TLB miss

- Get the page directory entry. If it’s not present in memory:

- Raise a page fault

- Ask the kernel for a frame

- Update the page directory entry’s present, read_write, and user_supervisor flags

- Get the page table using the PDE

- Get the page table entry from the page table. Add the entry to the TLB

- If the page table entry is not present in memory:

- Raise a page fault

- Ask the kernel for a frame

- Update the page table entry’s present, read_write, and user_supervisor flags

- Read the page from disk

- Check that the user has permission to perform the read or write operation. If not, raise a segfault and return

- Use the page table entry’s base address and the offset of the virtual address to compute the physical address. Get a physical pointer from this address

- Perform the read or write operation

- Mark the PTE as accessed. If writing, also mark it as dirty.

- Once you understand these steps, turn them into code. Then, test with the given test cases.

The rest of this documentation will serve to help you understand the purpose of each file and give you a high level understanding of virtual memory. The implementation details of each function are documented in the header files. The recommended sequence of reading the provided files will follow the sequence of files introduced in this documentation.

Simulated vs Actual Memory Spaces (types.h) #

In this assignment, we are simulating 32-bit virtual memory spaces and 32-bit physical memory spaces. All simulated memory addresses, both virtual and physical, will be stored in addr32 variables. Note that once you translate a simulated virtual address into a simulated physical address, you will want to convert the simulated physical address into an actual memory address in your process space, so that you can read from and write to memory.

Page Directories and Page Tables (page_table.h) #

Each process has two levels of paging:

The top level page table is known as a page_directory and has entries (page_directory_entry) that hold the base address of page tables (beginning of a page_table).

Each of these page_tables hold entries (page_table_entry) that hold the base address of an actual frame in physical memory, which you will be reading from and writing to.

Each table entry in both the page_directory and page_table contain

- the base physical address of the lower-level paging structure

- metadata bits and flags

These metadata bits and flags are explained in detail in page_table.h. The actual layout is taken directly from a real 32 bit processor and operating system, which you can read more about in the “IA-32 Intel® Architecture Software Developer’s Manual”.

For illustrative purposes a Page Table Entry looks like the following:

In our simulation, each entry is represented as a struct with bit fields whose syntax you can learn about in a tutorial. The bit fields basically allows us to squeeze multiple flags into a single 32 bit integer.

For the purposes of this lab you are only responsible for knowing how the following fields works:

- Page base address, bits 12 through 32

- Present (P) flag, bit 0

- Read/write (R/W) flag, bit 1

- User/supervisor (U/S) flag, bit 2

- Accessed (A) flag, bit 5

- Dirty (D) flag, bit 6

You will need to read and update these fields in the table entries. Here are some helpful tips for correctly setting the bits:

- Once a

page_directoryor apage_tableis created, it will remain in physical memory and will not be swapped to disk. - Each segmentation has a

permissionsfield, and there is a permissions struct insegments.h. Ifpermissions & WRITEis not0, then it has write permission. Same is true forREADandEXEC. -

page_directory_entry’s should always have read and write permission - For the purposes of this lab, all

page_table_entrys andpage_directory_entrys will have theuser_supervisorflag set to1

Note: The naming scheme of “page directory” and “page table” is unique to this assignment. Typically, we just know them as “first level page table” and so on.

Note: Be careful when writing into bit fields! What happens when the value you try to write into a bit field is larger than the maximum value that bit field can store?

Translation Lookaside Buffer (tlb.h) #

The Translation Lookaside Buffer will cache base virtual addresses to their corresponding page_table_entry pointers.

The implementation and header is provided to you.

Make note of the use of double pointers (why do we need that?). You will need to check the TLB and update it everytime you translate a simulated virtual address into a simulated physical address. You will also need to flush the TLB during context switches.

The reason why our TLB caches page_table_entry pointers instead of physical addresses of frames is because you will need to update metadata bits when translating addresses.

Segments (segments.h) #

A process’ virtual address space is divided into several segments. You are familiar with many of these:

- Stack

- Heap

- BSS

- Data

- Code

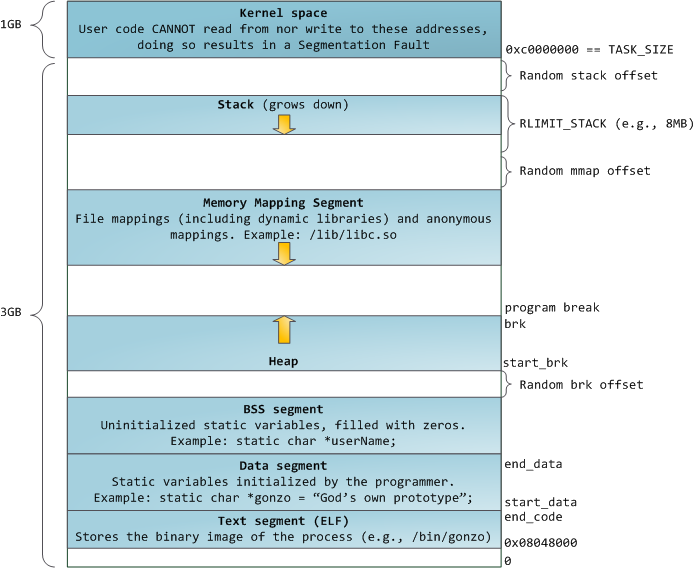

For this lab, a process’ address space is split into memory segments like so:

Photo Cred: http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory/

Notice how some of the memory segments like the stack and mmap have an arrow pointing down. This indicates that these regions “grow down” by decreasing their end boundary’s virtual address as you add elements to them. This is so that the stack and heap can share the same address space, but grow in different directions. It is now easy to see that if you put too many elements onto the stack it will eventually run into heap memory leading to the classic Stack Overflow.

The reasons why this external structure is needed for this lab is to answer the question: “How do you know when an address is invalid?”.

You cannot rely on the present bit of a page table entry, since that page may be valid, but just happens to be paged to disk.

The solution is to check to see if an address is in any memory segment with bool address_in_segmentations(vm_segmentations *segmentations, uint32_t address);.

If the address is not in any of the process’s segments, then you get the dreaded segmentation fault (segfault).

Note: There is one other form of segfault. Can you determine what it is?

Kernel (kernel.h) #

For this assignment all the memory allocations will be abstracted by kernel.c.

This file will maintain a global array of pages that you will use to model all of physical memory. That is to say that all simulated virtual addresses get translated to an address in:

char physical_memory[PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE] __attribute__((aligned(PAGE_SIZE)));

The caveat to this lab is that it is all done in user space. That means you are technically mapping one virtual address to another virtual address that represents a physical address. However, all the concepts involved remain the same in a real operating system’s memory management software.

We use a global char array for our physical memory as it so happens that global variables such as these are stored

in some of the lowest addresses in memory. Because of this, the array, despite existing in a 64-bit environment, only

needs the 32 lower bits of a 64-bit address to address it. This is great because it allows us to use 32-bit addresses to

refer to a simulated physical memory location, despite being on a 64-bit system. The downside is that we will need to convert

any 32-bit simulated physical memory addresses, which are stored as addr32 variables, into 64-bit void * pointers before we actually try to access that memory. We have provided a few helper functions to help with this conversion:

void *get_system_pointer_from_pte(page_table_entry *entry);

void *get_system_pointer_from_pde(page_directory_entry *entry);

void *get_system_pointer_from_address(addr32 address);

Examples usages of these helper functions can be found in some of the implemented features in mmu.c.

Note: Shifting signed numbers can produce unexpected behavior, as it will always extend the sign, meaning if the most significant bit is 1, the “leftmost” bits after shifting right will all be 1s instead of 0s.

Do yourself a favor, work with unsigned values.

Memory Management Unit (mmu.c and mmu.h) #

For this assignment you are only responsible for handling reads to and writes from virtual addresses. The functions you are to complete are:

void mmu_read_from_virtual_address(mmu *this, uintptr_t virtual_address, size_t pid, void *buffer, size_t num_bytes);

void mmu_write_to_virtual_address(mmu *this, uintptr_t virtual_address, size_t pid, const void *buffer, size_t num_bytes);

This means you have to translate a simulated virtual address into a simulated physical address, then read from/write to that memory location.

The following illustration demonstrates how to translate from a virtual address to a physical address:

This image is saying that you are to take the top 10 bits of the provided virtual address to index an entry in the page directory of the process. That entry should contain the base address of a page table. You are to then take the next 10 bits to index an entry the page table you got in the previous step, which should point to a frame in physical memory. Finally you are to use the last 12 bits to offset to a particular byte in the 4kb frame.

Testing #

Make sure you throughly test your code as usual. We have provided some tests cases, but we encourage you to write your own as well. Use the provided test cases as a reference to learn to create tests with good coverage.